1914 saw the start of a new type of war, where technological advances in weaponry reshaped the battlefield into an unforeseen nightmare. The Great War is cited as the first modern, mechanized war, its impact reverberating far beyond the toll of almost ten million soldiers lost. Another twenty-one million who survived would be irrevocably changed by their injuries, both physical and psychological.

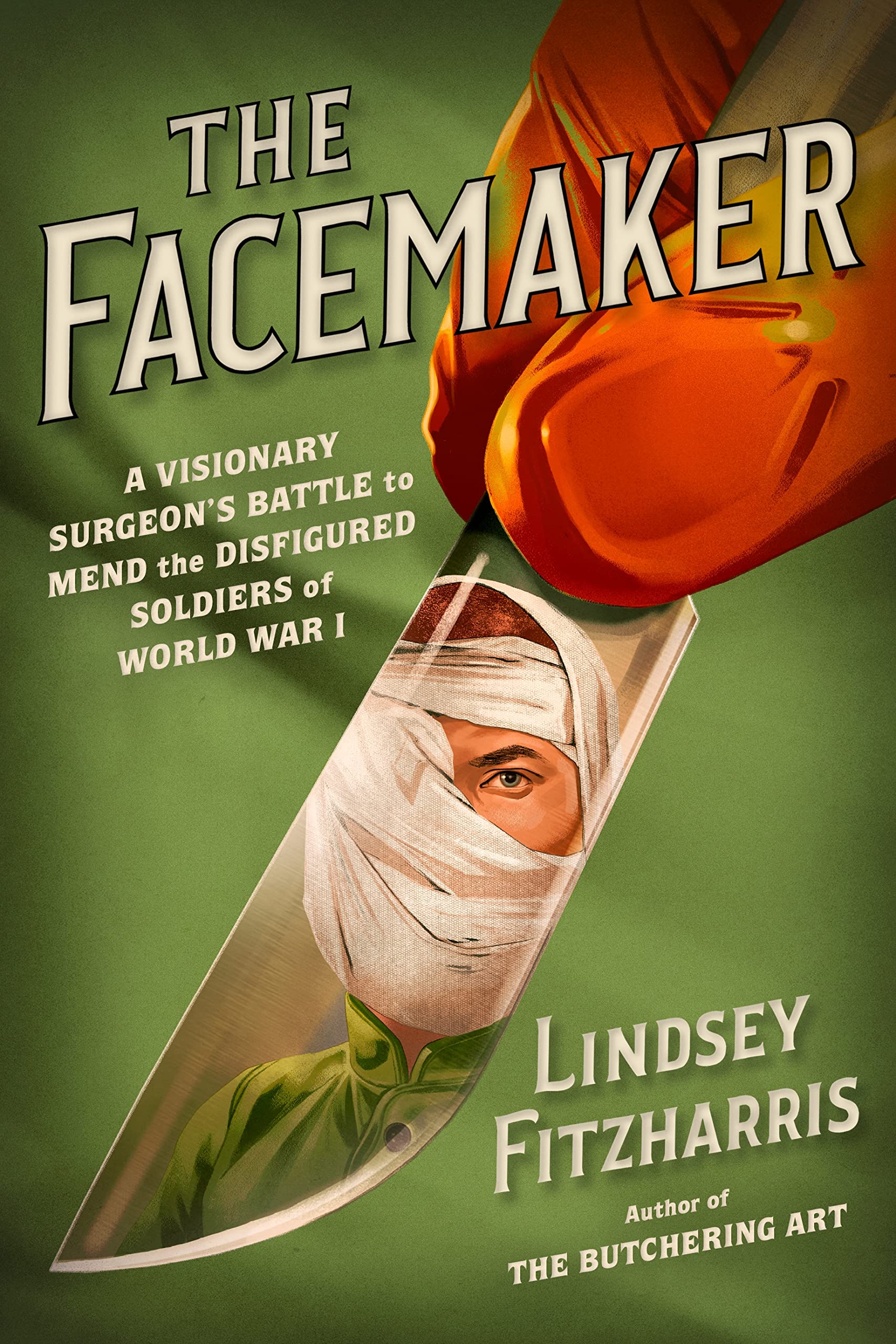

There are countless books detailing the carnage of field hospitals and trenches, the suffering inflicted upon those who fought in the war, and for what seemingly grand purpose their sacrifice served. Lindsey Fitzharris does touch on all of these topics, but the focus of her book “The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I” is the father of modern plastic surgery, Dr. Harold Gillies, and his groundbreaking efforts to mend both the faces and spirits of those disfigured in battle.

Fitzharris chronicles the life of Gilles alongside the experiences of several soldiers who would be placed in his care at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup. Gillies established this hospital as the first of its kind dedicated to facial reconstruction and rehabilitation. The advent of plastic surgery happened here, through the efforts of not only Gillies, but the remarkable team of surgeons, dentists, artists, photographers, and nurses whom he recruited for this endeavor.

This book is harrowing, understandably so for World War I, and the inclusion of photographs documenting the reconstruction progress of Gillies’ patients was not a choice Fitzharris made lightly. She notes that these disfigured soldiers would be hidden from the public due to the nature of their injuries, and it would be impossible to grasp the severity of their trauma, as well as the magnitude of Gillies’ skill, without seeing their faces during this process.

However, “The Facemaker” is not entirely a graphic tale about the horrific consequences of war. Fitzharris draws from primary sources to establish Gillies as a compassionate, dedicated surgeon; the doctor would personally visit his patients and instill in them a sense of hope and security during their recovery. The plastic surgery we know of today exists in part due to Gillies’ sincere efforts to heal his patients in both body and soul. His work didn’t end when a soldier was patched up just enough to survive, nor did it end when his face was reshaped to pass as “normal”. Gillies’ concern was rebuilding the face into what it once was, as it would be recognized by the soldier himself and his loved ones.

As the book explains, this was not the standard of the time; it was Gillies’ motivation to do his best for the soldiers in his care that brought about this monumental effort of aesthetic restoration. “The Facemaker” is a book I would recommend to those whose knowledge of World War I ends on the battlefield, and for anyone with a strong interest in innovators motivated by empathy. Anyone curious about the remarkable origins of something now so common place in our society would benefit from this book.