On April 24th, 1915 the Ottoman Empire began its systematic annihilation of the Armenian people with the arrest and deportation of Armenian leaders from Constantinople. The ensuing genocide resulted in the deaths of at least 600,000 Armenian men, women, and children before the First World War was over. The toll is estimated even higher, with 1.5 million people believed to have perished during the death marches across the Syrian Desert, if not later in concentration camps. To this day, the Turkish government denies that the genocide occurred, despite documentative evidence, and against the recognition by 34 countries of this period of deportation, imprisonment, and massacre as being an ethnic cleansing of the Armenian people.

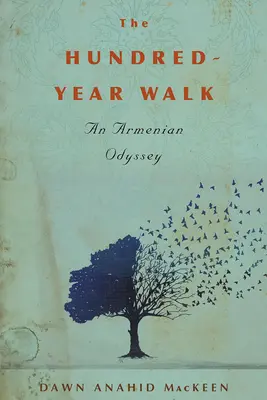

In “The Hundred-Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey“, journalist Dawn Anahid MacKeen travels from her family home in Los Angeles, California, to the places in Turkey and Syria where her maternal grandfather, Stepan Miskjian, endured persecution by the Ottoman Empire a century prior. The chronicling of Dawn’s journey is interwoven with Stepan’s first-hand experiences that he documented in what became two journals of writing, describing his arrest, separation from his family, and ultimately his escape from the destruction of his home. In the present day, Dawn uses these journals to navigate a very different land than the one Stepan was able to flee from.

Though most people she encounters during her travels overseas are friendly, she is reluctant to disclose her heritage and her motivation- to retrace her grandfather’s steps during a genocide continuously denied by the Turkish government. She is aware of the very real danger that accompanies speaking the truth, as there have been citizens arrested and even killed over the crime of “insulting the Turkish nation.” But Stepan’s journals, translated through a tremendous collaborative effort on the parts of Dawn, her mother, and the Armenian diaspora of their community, recount history in heartbreaking detail, being both clear evidence of the genocide, and a personal testament to Stepan’s grief and loss.

The content of “The Hundred-Year Walk” is distressing, but important to understand. Over a century between the start of the genocide and today means there are very few survivors alive to tell their stories. Descendants like Dawn must preserve the history of the generations before them, and it is the responsibility of all citizens of the world to learn this history in order to prevent such an atrocity from repeating. The reality is, of course, that two decades after the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust would begin along with a second World War, and once again, populations would be decimated by systematic massacre.

As someone who was taught about the Holocaust many times over in school, with the repeated affirmation to Never Forget such events occurred, it was astonishing that my first exposure to the Armenian genocide was not during any class, but instead from a dear friend, born to an Armenian family that carried the burden of retelling their own tragic history. This book is one I would recommend to those who are seeking to understand an often overshadowed period of history, and to those who understand the power of generational stories. The existence itself of such a book serves an important and hopeful message; it was because of her grandfather’s survival amidst atrocity that the author would be born to write this memoir, and share it with the world.