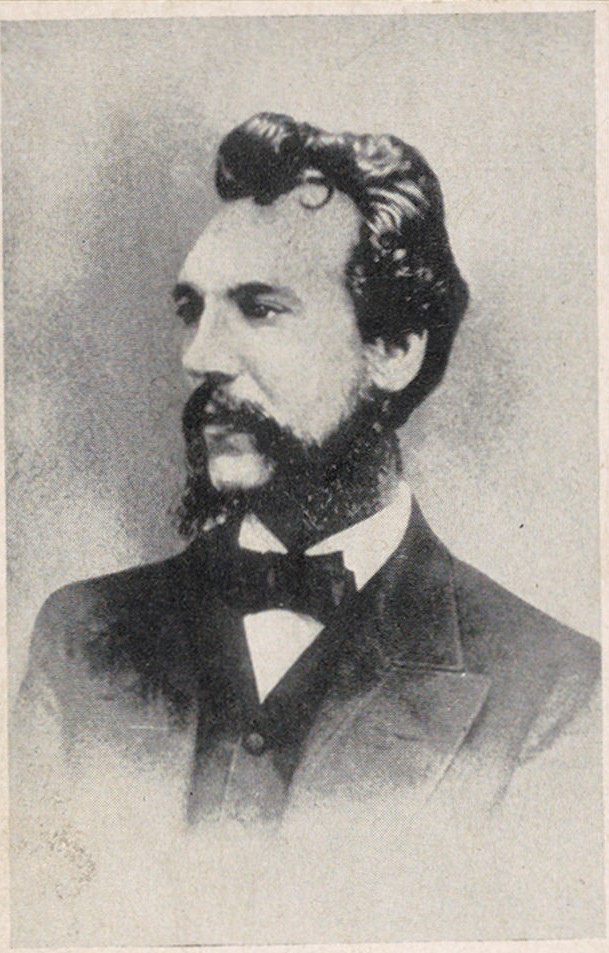

Photograph of Alexander Graham Bell from 1876, the same year he was granted his original telephone patent.

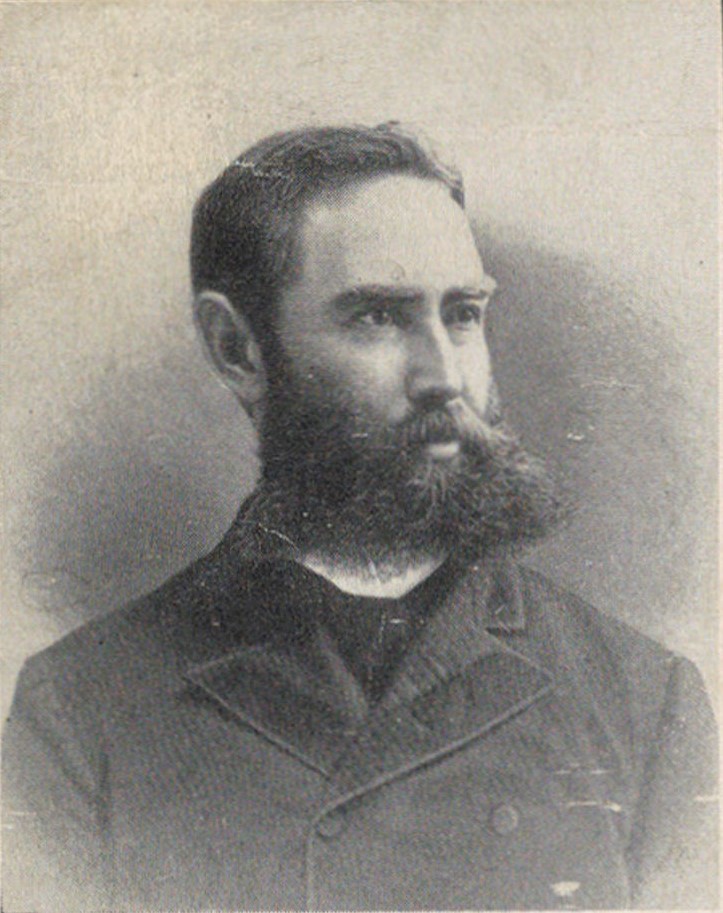

Thomas Sanders of Haverhill, MA

On April 1, 1871 Alexander Graham Bell was hired by principal Sarah Fuller to teach at the Boston School for the Deaf to show her teachers how to adapt Visible Speech for teaching the deaf to speak. Today it’s the Horace Mann School for the Deaf and is the oldest public day school for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in the United States.

After Bell’s first term lessons ended May 13, 1871 he went on to the Clarke Schools for Hearing and Speech in Northampton, MA and the American School For the Deaf in Hartford CT. It was at the Clarke School where authorities reported that in a few weeks he taught the children to use more than 400 English syllables, some of which they had failed to learn previously under other methods of teaching.

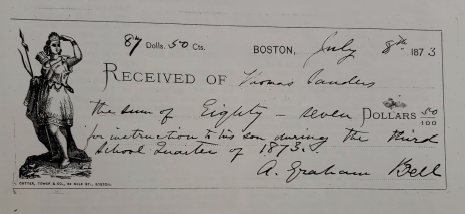

In October 1872 Bell opened a school of Vocal Physiology and Mechanics of Speech at 35 West Newton St, Boston, MA. This is where Bell met Haverhill native 5 year old George “Georgie” Sanders, son of successful leather merchant, Thomas Sanders. Impressed with his teaching, Sanders arranged that George should live with his grandmother in Salem, and that Bell would board with her. Believing this being the most convenient arrangement to continue George’s instruction. And, as it would turn out, this arrangement would become very profitable for Alexander Graham Bell and his inventions.

During the three years that Bell taught George Sanders, Bell was conducting experiments which resulted in two patents. The first was No. 161,739 issued on April 6, 1875, for an Improvement in Transmitters and Receivers for Electrical Telegraphs; the other was No. 178,399, issued on June 6, 1876, for Telephonic Telegraph Receivers. Meanwhile his teaching of the Sanders boy had been so successful that Thomas Sanders, in gratitude, had offered to meet all the expenses of his experiments and patents, running $100,000 in debt to help launch the telephone. As a result, Mr. Sanders became the first treasurer of Bell Telephone.

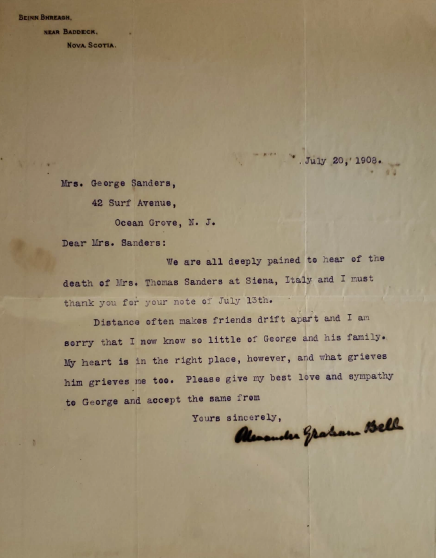

Even after the invention of the telephone and Bell’s newfound fame, he continued to keep close contact with the Sanders family and George in particular, who he had taught for two decades. Bell attended George’s grandmother’s funeral where he met his future wife Lucy Swett, a young Deaf woman from a multi-generational Deaf family influential in the New England Deaf community. The two were very much in love, but their courtship brought the Deaf-Deaf marriage debate to Bell in a way he had not anticipated. He was forced to confront matters of life and love among those he considered closest to himself. Bell wrote to his wife after the funeral of the elder Mrs. Sanders and mentioned George and Lucy “I’m afraid the attachment has become too strong for prudence to have sway. They will surely marry–But what then? Will lovers ever consider the good of those that will come after them?” Bell having the opinion that their courtship was improper for hereditary reasons: “George chooses danger to his offspring–for her love.” Immediately following with, “Yet I can understand it too.”

George and Lucy Sanders did marry and had two children, Dorothy Bell and Margaret, who were both deaf.

The family in DC, Dorothy age 5 and Margaret Age 3 c. 1890

Photo of Lucy “Captures her personality unlike any other photo. Jolly” -Margaret

Lucy’s great-uncle, Thomas Brown, was the organizer of the first large-scale gathering of American Deaf people in 1850. Her father William Swett, was the co-publisher of the Boston-based Deaf periodical, the “Deaf-Mute’s Friend,” and founder of the Beverly School of the Deaf. Mr. Swett was a deaf man with a deaf daughter and saw a need for educational and vocational services for deaf children and young adults of Boston’s North Shore. The school was initially run by the Swett family with Mr. Swett as the Superintendent, and Mrs. Swett as the Matron and 30 students. Their daughters Nellie and Lucy became teachers. Today, services have been extended to students with Autism, developmental delays, and other disabilities and is known as The Children’s Center for Communication with Beverly School for the Deaf.